Write to us:

We live in the era of the binge. Seasons drop all at once, devoured in a single, slightly sleep-deprived weekend. A “Next Episode” button now decides whether we go to bed or watch “just one more.”

But before streaming queues and algorithms curated our tastes, television was an event. It was “appointment viewing.” You didn’t choose when to watch a show—the network did. And if you missed it, you missed it. No instant replay, no legal streaming the next morning, no spoiler-free zone on social media to catch up later.

In the 90s, if you missed last night’s episode, you weren’t just out of the loop—you were socially offline. The hallway chatter, the office coffee break, the schoolyard debates all revolved around what aired at 8 PM the previous night. Television didn’t just fill time; it structured it. Nowhere was this truer than in Eastern Europe, where American imports became cultural earthquakes.

The Soap Opera Invasion: Dallas and The Bold and the Beautiful

If you grew up in the Balkans in the late 1980s or early 1990s, your introduction to “big TV” probably didn’t start with quirky aliens or FBI agents. It started with oil, shoulder pads, and cliffhangers.

Before Netflix, before even “ALF” in many households across Yugoslavia, Bulgaria, Romania, Albania, Greece, and beyond, there was “Dallas” and later “The Bold and the Beautiful.” These weren’t just TV shows, they were windows into another universe, one where people had endless money, endless drama, and kitchens bigger than most apartments.

The broadcast itself was an event. Streets went quiet when “Dallas” aired. Families gathered around a single TV set, sometimes with neighbors squeezed in, all waiting to see what JR would do next. You didn’t just watch “Dallas“; you scheduled your life around it. If you missed an episode, you didn’t just lose the plot—you lost your footing in everyday conversations.

By the time “The Bold and the Beautiful” arrived, the pattern was already set. These glossy half-hour doses of romance and betrayal became daily rituals. Theme music signaled more than the start of an episode, it signaled a pause in the day. Shops would half-close, chores went on hold, and for 20–30 minutes, the Balkans collectively teleported to Los Angeles fashion houses and tangled family trees.

Dubbed voices, slightly off-sync, became iconic in their own right. Local expressions leaked into translations. In some places, people quoted lines in the dubbed versions, not the originals. These shows stitched themselves into everyday language, jokes, and even moral debates: Who’s right? Who’s wrong? Could anyone ever be as dramatic as these people?

For a region in political and economic transition, the contrast made them even more hypnotic. The gap between what you saw on screen and what you saw out your window was enormous—and that tension made the viewing communal. It wasn’t just escapism, it was a shared fantasy, processed together, episode by episode, over kitchen tables and coffee cups.

The Sitcom Anchor: ALF

Before prestige dramas and complicated anti-heroes took over, we had a furry alien from Melmac who ate cats.

“ALF” is peak bizarre 80s/90s sitcom energy: laugh track, wild premise, and a character so merchandisable he might as well have been born in a marketing meeting. But for all its absurdity, “ALF” did something important—it anchored the evening.

You knew exactly when it came on. Families gathered on the couch at a specific hour, tuned to a specific channel, with zero control beyond the volume and maybe the color settings on the TV. The remote, if you even had one, was basically a ceremonial object.

There was no “Skip Intro” button. The intro was the ritual. The static crackle as the CRT TV warmed up, the station ident, the theme song—those were the opening ceremonies of the night. By the time ALF had crashed into the Tanner family’s garage, you were already locked into a shared experience with millions of strangers doing the exact same thing in other living rooms.

It wasn’t just a show, it was a weekly family checkpoint.

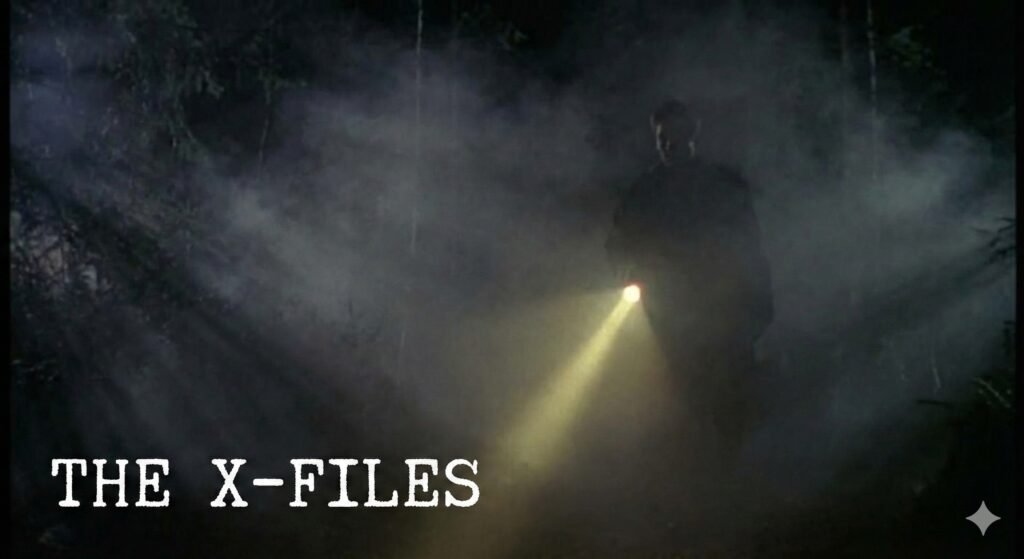

The Sci-Fi Shift: The X-Files

Then something shifted.

“The X-Files” didn’t just air; it hovered. It had a mood, a texture. From the eerie theme song to the cold, dim lighting, it felt more like a low-budget horror movie each week than a traditional TV drama.

Mulder and Scully brought a new language to television—more cinematic, more ambiguous, and way more paranoid. The show taught an entire generation to question authority, distrust government files, and look nervously at the sky whenever a strange light appeared.

But the real magic wasn’t just the stories; it was the wait.

If an episode ended on a cliffhanger, you had seven days to sit with it. Seven days to replay scenes in your head, argue fan theories with friends, and circle the next air date in TV Guide. That week-long gap was part of the experience. It made the unknown feel bigger, the mysteries heavier, the payoff more satisfying.

Streaming can give you the next episode in three seconds, but it can’t give you a week’s worth of shared anticipation.

From Anticipation to Immediacy

Shows like “Dallas,” “The Bold and the Beautiful,” “ALF,” and “The X-Files” belong to a very specific era of TV, the in-between space where television was still communal, but starting to get more complex and cinematic.

We’ve obviously gained a lot since then. We can watch almost anything, anytime, on any device. Missed it? No problem. Watch it tomorrow, or next year. We’re never locked out of the conversation for long.

But we traded something in that process.

We traded the thrill of anticipation for the convenience of immediacy. The friction is gone, and with it, some of the ritual. There’s no static hum before the episode, no weekly countdown, no “Did you see it last night?” urgency in the hallway.

Maybe nostalgia is just our way of remembering what it felt like when TV wasn’t just content, but an event you built your evening around. When oil barons, fashion moguls, furry aliens, and two FBI agents could quietly rearrange how we watched, talked, and even believed.