Write to us:

If you were a teenager in the late 90s, you didn’t want an iPhone. You wanted a Sony.

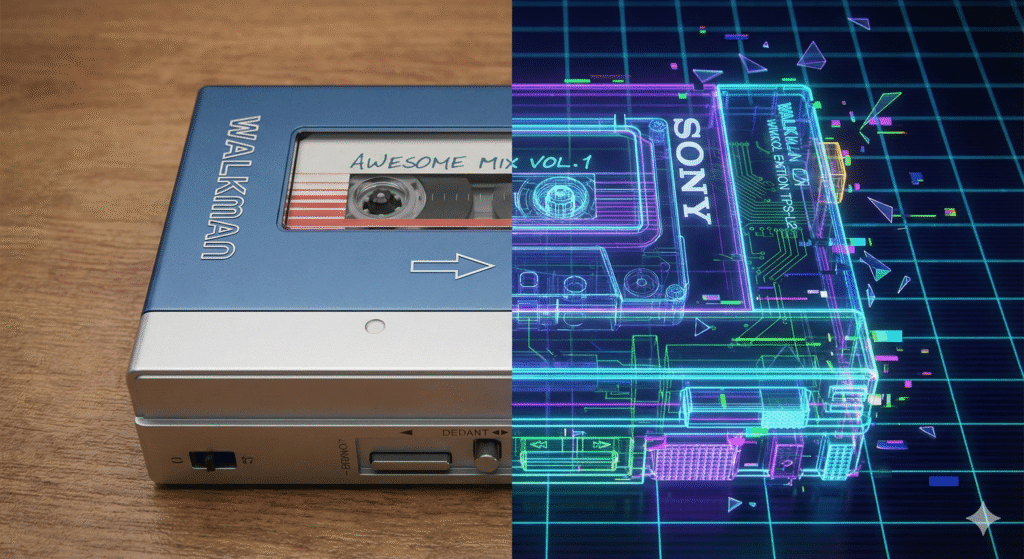

Before the white earbuds of Apple conquered the planet, there was only one king of portable audio. Sony. They gave us the original Walkman in 1979, changing the way the human species interacted with cities forever. Suddenly, life had a soundtrack.

But in the awkward transition period between the cassette tape and the MP3 file—roughly 1992 to 2001—Sony tried to build the future. And they built it beautiful, complicated, and ultimately doomed.

This is the story of the MiniDisc, the Memory Stick, and how the company that invented portable music forgot to listen to the music.

The Cyberpunk Dream of the Sony MiniDisc

If you look at a MiniDisc (MD) today, it still looks more “future” than a Spotify playlist. It was a small, encased optical disc, roughly half the size of a CD, protected by a hard plastic shell and a sliding metal shutter.

It looked like something Keanu Reeves would smuggle data on in Johnny Mnemonic. It had a satisfying, tactile clackwhen you loaded it into the player.

Technically, it was a marvel.

- It was digital: Near CD-quality sound.

- It was recordable: Unlike CDs, you could record, erase, and move tracks around instantly.

- It was shock-proof: Sony developed a buffer memory that read ahead, so even if you jogged, the music didn’t skip.

For a brief moment in the mid-90s, it felt like this was it. This was the format that would replace the cassette. But Sony made a fatal miscalculation. They fell in love with the hardware, while the world was falling in love with the software.

The Fatal Flaw: The Fear of MP3

Why isn’t the Walkman the dominant device today? Why is “Sony” not the name on the back of your smartphone?

The answer lies in one word: Control.

In the late 90s, the MP3 format exploded. Napster arrived. People were ripping CDs to their hard drives. It was the Wild West. Sony was in a unique, paradoxical position:

- They were a Tech Giant making players.

- They were a Music Giant (Sony Music) owning the rights to Michael Jackson and Mariah Carey.

These two halves of the company were at war. The Hardware division wanted to make MP3 players. The Music division was terrified of piracy.

The compromise? ATRAC.

Instead of letting you simply drag and drop your MP3 files onto a Sony player (like the later Network Walkman), Sony forced you to use their proprietary software, SonicStage, to convert your MP3s into their proprietary format, ATRAC.

If you ever used SonicStage, you know the horror. It was slow, it crashed, and it locked your music to your device. It was a digital prison.

The iPod Event Horizon

While Sony was busy building beautiful, physical fortresses for their music (MiniDiscs, Memory Sticks), Apple looked at the problem differently.

Steve Jobs realized that people didn’t want to carry discs. They didn’t want “physical media” at all. They wanted their entire library in their pocket.

In 2001, Apple launched the iPod. It was inferior to Sony in sound quality. It was expensive. But it had FireWire, it synced effortlessly, and it didn’t care where your MP3s came from.

The comparison was brutal:

- Sony: “Here is a cool cyberpunk disc that holds 74 minutes of music. You have to carry a bag of them.”

- Apple: “Here is a thousand songs in your pocket.”

The Legacy of the “Almost” Future

Looking back through the glitchy lens of nostalgia, there is something deeply charming about Sony’s failure.

The MiniDisc players were masterpieces of engineering. They were dense, metallic, and intricate—marvels of Japanese miniaturization. Holding a Sony MZ-N10 feels like holding a piece of precision jewelry. Compare that to the disposable plastic feel of modern gadgets.

Sony’s “smart” gadgets weren’t dumb. They were just too arrogant. They tried to dictate how we consumed media, rather than adapting to how we wanted to consume it.

Today, we collect these devices not because they are useful, but because they represent a timeline that split. A timeline where physical media survived, where we still pushed buttons, and where the music had weight.

Sony didn’t lose because they lacked technology. They lost because they tried to build a wall around the internet. And the internet always wins.

Next Step: Do you still have an old Walkman in a drawer? Dig it out. The battery might be dead, but the aesthetic is immortal.